Recently, I gave a talk at Bart’s Pathology Museum in London on the Victorian attitude towards ancient Egyptian mummies. The event was sponsored by Hendricks , the gin manufacturers.

In the 18th century London, gin was often termed ‘mother’s ruin’, due to its then apparently deleterious effects on the health of its consumers, and women in particular. So it seemed apposite that the title ‘Mummy’s Ruin’ be given to the talk and this article, which is a record of some of my comments made during the talk. After you read about what happened to some of these mummies I feel the title ‘The Ruin of Mummies’ may also be appropriate!

I would like to thank Hendricks for supporting the event so ably, though, in no way can they be blamed for the ruin of some ancient Egyptian mummies, described below.

Like many people of today, the Victorians were fascinated by ancient Egyptian mummies and they yearned to discover the secret of their preservation. How the Victorians went about investigating these mummies, however, was radically different to the research approaches undertaken nowadays. This article will outline the early European experience of Egyptian mummies and how some Victorians dealt with mummies, including a peek at two rather interesting examples.

Mummies in Theatre

Europe’s awareness of ancient Egyptian mummies can be demonstrated from centuries ago; a perusal of early English plays, for example, testifies to this. In Shakespeare’s Macbeth we read of ‘witches’ mummy, maw and gulf’ (note 1), whilst Webster wrote:

‘Your followers

Have swallowed you like mummia, and, being sick,

With such unnatural and horrid physic,

Vomit you up in the kennel…’ (note 2)

Thus, it is clear that Europe by this time already had an association with Egyptian mummies and had developed a belief in their curative powers, for bits of ancient Egyptian mummies were being ingested! The term mummy is actually derived from mumia, a medieval Latin word (borrowed from a medieval Arabic word), meaning a corpse preserved by embalming.

Mummies as Medicine

Medieval Europeans associated the seemingly incorruptible nature of these mummies with the ability to confer longevity and good health. If these ancient people could ‘exist’ (through their mummification) into the then ‘modern’ era(s) then surely they contained the secret of life – this was the medieval way of thinking. Surely, they thought, these ancient preserved individuals could cure illness and disease! It was not unusual for medieval physicians to prescribe the ingestion of mummies as a medicine. One such man was Ambrose Pare, a 16th century French surgeon who treated several French monarchs. He was a pioneer in his field and yet, like many doctors of his time, offered practical treatment together with the philosophy that God had an important part to play in the healing process. He is said to have used mummy in his treatments – seemingly he associated the bituminous materials on mummies with antiseptic properties, which it actually does have. Centuries before Pare, the polymath Avicenna (Ibn Sena) wrote over forty treatises on aspects of medicine and he clearly had great faith in the curative powers of mummies. Living in the late 10th century, he prescribed mumia (mixed with wine or oil or milk) as a cure for a great number of ailments including fractures, abscesses, disorders of the stomach, liver and spleen and also as an antidote to poisons.

Even royalty believed in the curative powers of mummy medicine. History records that the French monarch Francoise I rarely ventured far without a small pouch containing a mixture of mummy powder and pulverised rhubarb, so strongly did he believe in the mixture’s efficacy in curing a large range of ailments – from bruising and headaches to major diseases! Interestingly, modern research indicates that rhubarb does indeed benefit health, being useful for improving the digestive system, lowering cholesterol levels and boosting the immune system but, whether or not Francoise knew this is not recorded; restoration of health through eating bits of ancient dead bodies, however, has yet to be proven!

The practice of using ground up mummy parts was not, however, without its critics. In the late 16th century, the traveller, writer and ordained priest, Richard Hakluyt, complained :

‘these dead bodies are the Mummy which the Phisistians and Apothecaries doe against

our willes make us to swallow….’

Nevertheless, this interest in the ‘power’ of Egyptian mummies promoted the procurement of them – merchants would import them and even travel to Egypt to purchase them. Unfortunately, hundreds of these mummies were taken apart when the presence of valuable jewellery, amulets and papyrii within the wrappings was realised and, as a consequence of this, there was a ready supply of mummified body parts to be used in medicines (figs. 1 and 2); this eagerness to procure Egyptian mummies continued into the 20th century.

Even more bizarre was the fact that, so smitten was Europe with purchasing Egyptian mummies that, ‘fake’ mummies were bought and brought into Europe. Business-minded (modern) 19th and 20th century Egyptians and foreign merchants actually buried recently deceased Egyptians in the hot sands of Egypt to dry them out and later dug them up and sold them as the genuine ancient Egyptian article! These were then used in the mummy-for-medicine trade. Incidentally, whole mummies were also used on railways, as a cheap form of fuel; mummy parts were also a basic ingredient in the composition of oil paint known as mummy brown (fig. 3) and because of their colour mummy parts were incorporated into the making of brown wrapping paper.

Mummies and Napoleon

In the late 18th century, Napoleon Bonaparte initiated a survey of ancient Egyptian artefacts, including monuments, works of art and, of course, mummies. The expedition which undertook this mammoth task included leading scientists, geologists and naturalists, amongst many. The findings of this survey were published in 1809 as Description de l’Egypte and even further brought the presence of mummies to the attention of Europeans. The work, originally in many volumes, features carefully executed engravings of the items surveyed. Many of the mummies found were brought into Europe – but what happened to them?

Mummies and Victorian England

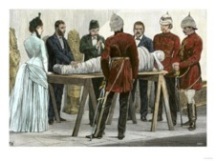

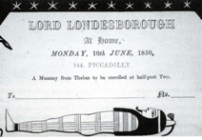

In the 19th and 20th centuries it was not unusual for a wealthy family to own an Egyptian mummy; often they were exhibited in the family library, or elsewhere, for visitors to admire. As stated above, it is clear the Victorians and Edwardians were keen to discover how these mummy packages were put together. The fashion arose whereby guests would be invited to the home of a mummy owner (fig. 4), perhaps for a meal, with the entertainment being the investigation of a mummified body. These events were termed ‘mummy unrollings’ as there was an attempt to denude the mummy of it’s linen wrappings. Nowadays, such practices might be termed an autopsy or dissection for, inevitably, the body within was taken apart in the attempt to discover it’s secrets of longevity. Many hundreds of mummies were destroyed this way, never to be seen again; rarely were records of these unrollings kept and so the information is lost to us forever. It was not unusual for pieces of linen wrappings, bits of bones and other body parts and items found within the mummy packages to be given to those attending the unrolling event (fig. 5).

The presence of fashionably dressed society ladies in oil paintings of the time clearly underline the ‘entertainment’ value of the event (note 3). Fortunately, however, on a few occasions, the ‘unrollers’ wrote down their thoughts and findings.

One notably recorded mummy autopsy took place in London, in April, 1825. In 1821, the mummy of a female together with its (probable) inner coffin, had been purchased by Sir Archibald Edmonstone, for 4 dollars. Edmonstone donated the mummy and coffin to Augustus Granville, a noted physician and obstetrician to the Duke of Clarence. Granville undertook a public autopsy of the mummy before an audience of the Royal Society of London and he published his findings in 1825 (note 5). Following his dissection of the mummy, Granville mounted specimens taken from the body and mounted them in a specially designed box containing trays (fig. 6) and a drawer to hold the samples (note 6).

In his publication, Granville imagined that the lady had lived during the time of the Middle Kingdom king Sesostris I, however, a modern examination of her coffin indicated that it had been made during the Persian period of Egyptian history, a much later date in time – but still very ancient; suggesting that the woman was alive at about 600 BC. Granville’s examination revealed that the:

‘female of which we are speaking, died at an age between fifty and fifty-five years; that

she had borne children; and that the disease which appears to have destroyed her was ovarian

dropsy attended with structural derangement of the uterine system generally…’ (note 7)

However, in the 1990s , analyses of lung tissue contained in one of the sample trays indicated she had died of pneumonia and an examination (note 8) of the extant reproductive organs (held in one of the trays) indicated the presence of a benign tumour, not life threatening to the lady but certainly one of the earliest examples of a soft tissue tumour in medical history! Further publications on this autopsy are soon to be available.

Another interesting example of the Victorian (or Edwardian) treatment of mummies produced a very interesting project for the author. This paragraph will be brief, as the full version is due to be published (note 9). Some years ago, a mummy and a coffin arrived in London to be sold at auction. The author was asked to examine and report upon the contents. The coffin contained a mummy but this had been plundered some time previously (evidence for this is being further investigated) with the body having been ripped apart at the midriff area. Most of the bones were extant and so the body was re-articulated; an anthropological report on the remains is to be published (also note 8). Of pertinence to this article is the fact that it was clear that the mummy’s face had been altered, probably in Victorian (or Edwardian) times. The linen wrappings covering the face had been cut out in an oval shape revealing the then mummified visage – over time the skin had decayed and fallen off, leaving merely the bony skull poking out of the wrappings; an attempt to make the mummy more acceptable to the then modern audience? This seems likely as the mummy and coffin were probably displayed upright in the European owner’s home!

Nowadays, mummies are not generally unrolled or autopsied in order to discover their secrets; CT scanning, a non-invasive method of examining bodies, is a costly but preferred method. The author has had the privilege of leading many projects CT scanning ancient Egyptian mummies; for example, some brief notes on the examined mummy of a man named Artemidorus can be seen elsewhere on this site (note 10) and, in due course, further reports on my findings in a number of mummies will be published (see also note 9).

This article, hopefully, has briefly outlined some of the issues concerning the ruin of ancient Egyptian mummies.

Notes and references:

1. Macbeth, 4:1:23.

2.The White Devil, i. 1, 143.

3. Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holder of this image. If the copyright holder would contact me then I would be happy to acknowledge/edit my article accordingly. Also, a particularly fine example of such an oil painting can also be seen in Joyce Filer (1995), Disease, London: British Museum Press, colour plate IV.

4. Granville reported that there was no outer coffin; nowadays, only the lid is extant

5. Augustus Bozzi Granville, 1825, An Essay on Egyptian Mummies; with observations on the art of embalming among the ancient Egyptians, London: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.

6. I would like to thank the Trustees of the British Museum for kindly allowing me to examine and record the extant samples of this mummy during my time there.

7. Granville, ibid, 1825, p. 298

8. by Dr. E. Tapp, a specialist in morbid anatomy examination

9. This mummy, together with other fascinating examples, is to be published in Joyce M. Filer, Beneath The Bandages: essays on ancient Egyptian Mummies, Rutherford Press, forthcoming

10. see Archive June 2012 post: Artemidorus: an ancient murder mystery?