Akhenaten: a medical mystery?

The problems in interpreting images of Akhenaten

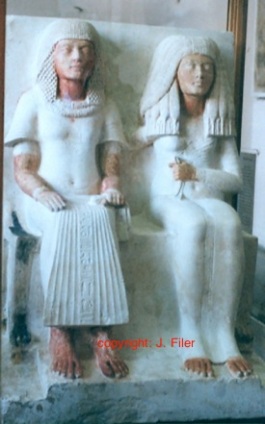

Ancient Egyptian royal statuary is easily recognisable – the classic features being the well-carved, proportionate and striding figure of the king often depicted with the supportive, but seemingly emotionally distant, figure of a wife or goddess. Other types of art, in the form of carved reliefs, are also easily recognisable by the proportions and attitudes of the figures. However, the art of the Amarna period (featuring the reign of Amenhotep IV or Akhenaten, c. 1353 – 1336 BC) marks a departure from the ancient Egyptian ‘norm’ with regards to this matter of proportion and in some cases to the types of subject matter portrayed. When examples of Amarna period art forms were initially studied decades ago, and the unusual physical features of the people depicted were noted, many medical historians had a field day postulating various pathological conditions that might have ‘afflicted’ Akhenaten (and his family) – some of these will be discussed below.

The question of squares

Before examining how the artwork of the Amarna period has been interpreted with regards to possible pathological conditions, it would be useful to outline how Amarna artwork differs from traditional ancient Egyptian artwork, especially with regard to depictions of the human body.

The rather ‘unusual’ depiction of the human form is seen in representations of Akhenaten, members of the king’s family and in courtiers. Whilst there are discernible changes in the ‘Amarna’ style as Akhenaten’s reign progresses, generally the upper torso is depicted small with a narrow waist and narrow shoulders; the stomach area protrudes. The lower parts of the legs appear shorter whilst the upper legs swell out to form curvaceous thighs and buttocks. The head, set on a longish neck, is seen as large with the facial features appearing to sag or droop (less so in non-royal individuals).

Some of these features of Amarna art are achieved through changes in the proportions of the figures depicted. Traditionally in ancient Egyptian artistic depictions, when a relief (carved and/or painted) was finished any background grid lines would be removed but, there are some examples of grids which were not removed and these reveal the number of squares used to execute the piece. Traditionally, in non-Amarna periods, eighteen squares were used between the feet and the hairline and the legs were shown as a third of the hairline height.

Whilst not many traces of the grid system used remain on Amarna reliefs there is enough extant evidence to reveal how these seemingly ‘disproportionate’ figures were achieved. A particularly revealing piece is a painted limestone relief from the royal tomb at Amarna, now held in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. The rectangular piece, 53 cm in height, depicts Akhenaten (identified by cartouches at the top of the sunken relief), Nefertiti and two of their daughters in the act of offering flowers to the Aten. Red grid lines can still be seen on the background stone behind the figure of the king. These grid lines reveal that twenty squares were used between the feet and the hairline. Thus, these two extra squares allowed for the changes in bodily proportions: one square for a longer neck, the other square for the protruding stomach; the height of the lower legs also appear shorter because they were depicted as less than a third of the of the hairline height. Thus, we see that figures during the Amarna period appear different from those of other artistic periods because of the different squared proportions used.

The question of subject matter

The difference in proportions, as alluded to above, is not the only outstanding feature of Amarna art. The subject matter depicted in Amarna reliefs differs somewhat from that seen in other periods of Egyptian art, especially with regard to the display of emotion. As stated above, whilst females (such as a wife) are depicted in Egyptian art there is often a lack of emotion displayed. True, in many statues and in some reliefs, the female figure (usually the wife) is often seen with an arm around the male figure but this might be interpreted as indicating a supportive role in the relationship rather than an actual emotional attachment. This is not to suggest that there were no emotional links between ancient Egyptian spouses but rather that such ‘events’ are generally difficult to discern! Art in the Amarna period, however, seems to represent a departure from this view. Of course there are the more traditional (fig. 1)

and formal court scenes depicted but, in several cases, we see Akhenaten openly displaying emotions towards his queen, Nerfertiti, and towards his children. A particularly interesting family life scene is depicted on an limestone altar stele (height 32.5 cm and now in Berlin) where Akhenaten and Nerfertiti are shown seated in a pavilion with three of their daughters. One daughter sits on Nefertiti’s lap, another is balancing against her left shoulder. Opposite them, Akhenaten holds a third daughter – remarkably he is kissing this daughter in a fatherly and openly affectionate way – a scene unprecedented in royal iconography from earlier periods! Whilst this shows a private family moment, the fact that the Aten disc is displayed above the family group also indicates that this piece is also a religious statement. Other pieces of royal art of this period show open affection between Akhenaten and his queen Nefertiti, incidences rarely seen in other periods

The question of pathology

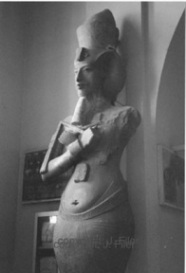

So, we can see that some Amarna art departs from the ‘norm’ in terms of proportion and subject matter. The art of the Amarna period is dominated by the figure of the king, Akhenaten, himself. We now have a number of statues representing this king and, whilst we admire the actual skill of the ancient craftsmen who sculpted these statues, the eye cannot but help but be drawn towards the somewhat unusual representations of the king’s face and physique (figure 3). His physique appears to show both male and female characteristics. The female characteristics are a narrow waist, pronounced breast and abdominal areas, wide hips and plump thighs, yet the wide shoulders appear male. His face is shown with unEgyptian features: elongated shape with a pendulous jaw, sunken cheeks and long, upward slanting eyes (figs. 2 and 3).

This very mix of features propelled many medical historians and other researchers to propose that Akhenaten suffered from a variety of medical conditions. Let’s examine some of these medical theories.

In biological terms an organism that has reproductive organs usually associated with both male and females genders is termed a hermaphrodite (nowadays, the term intersex is the preferred term as ‘hermaphrodit’e is thought to be misleading). That the representations of Akhenaten seem to show both male and female characteristics has encouraged some researchers to propose that the king might have been an hermaphrodite. There are several categories of disorders of sex development, most of which might prove difficult to ascertain for Akhenaten – even if we had human remains firmly attested as his! However, generally, true hermaphroditism in humans means that the individual has both ovarian tissue and testicular tissue resulting in ambiguously formed external and internal genitalia. For Akhenaten, if he was an hermaphrodite, there is no way of assessing (purely from artwork) any underlying tissue evidence and so any external ‘ambiguities’ cannot be linked inextricably to the condition. It would have been important to assess such information in connection with Akhenaten as, seemingly, he fathered children – but, of course, we cannot access such tissue information.

Froehlich’s Syndrome, a rare condition typically affecting mostly males, may also be known as adiposogenital dystrophy and is characterised by feminine-type fat distribution (breast, stomach and thigh areas), obesity, short stature and retarded sexual development and other features. It is suggested that the condition (and its variants) is caused by an endocrine abnormality which results in a number of symptoms. Such abnormalities might be impairment of the hypothalamus or a pituitary tumour. Again, for Akhenaten, we only have artwork to consider – we can see pronounced fatty areas of the stomach, thighs and breast but short stature is not apparent and neither can we assess sexual development from the extant artistic evidence. It is suggested that the syndrome may be acquired whereas related syndromes (such as Prader-Willi syndrome) are genetic, which may be why this was a popular ‘diagnosis’ for medical historians. It is important to consider that males affected by this condition rarely not grow facial hair yet, with regards to Akhenaten, there is a small relief piece in Germany depicting him with a stubbly beard; in Egyptian royal society being shown unshaved was a sign of mourning – we know one of Akhenaten’s daughters (with Nefertiti) died young -and this scene seems likely to have been one of mourning for the young princess. Thus, if Akhenaten had Froehlich’s Syndrome he would not have been able to ‘produce’ this stubbly beard!

Marfan syndrome is a disorder of the connective tissues, the fibres providing a framework for the body – thus, an affected individual’s body shape can become abnormal (to various degrees). Additionally, heart and lung problems may also feature in this condition and the individual’s eyesight might be affected through wrongly placed lenses, glaucoma and cataracts; these features cannot be established through the works of art under discussion here. More obviously, the disorder is shown through long limbs (including fingers and toes), an elongated and thin face, tall stature and sometimes curvature of the spine. Immediately, we can see why medical historians favoured this condition for the extant statues of Akhenaten – with their tall stature, long limbs and elongated facial features. Much modern research into the possible causes of this condition has been undertaken. Values for modern liveborn infants suggest that 1 in 4,000 individuals are affected, due to autosomal dominant factors (where only one mutated copy of the gene involved is necessary for a person to be affected by an autosomal condition). Overall, it is suggested that heredity plays an important role in the condition. We have a mummy thought to be that of Amenhotep III, Akhenaten’s father, but there are two issues here. Firstly, this mummy does not display similar features shown in Akhenaten’s statues and secondly, can we be so sure that this is the mummy of Amenhotep III? The identification of this mummy is subject to conjecture!

My view is this – no actual body = no confirmed disease! I have stressed that we only have Amarna artwork to study – so where is the body of Akhenaten? Many people would like it to be that found in tomb KV 55. I have examined that body, formerly a mummy but now skeletal remains. The body shows no external and obvious signs of unusual pathological conditions. Recent tests on bodies possibly related to Tutankhamun (in a research project led by Zahi Hawass) also seem to indicate that the KV 55 remains, regardless of his identity, did not ‘suffer’ from unusual pathological conditions.

I rest my case – for a while anyway!