Early in 2013, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) asked people to complete a survey identifying the birds in their gardens here in England. I filled in my survey and I hope others did too – it is important to record and protect our wildlife.

I thought it would be useful to write a companion piece offering some ideas about the range of birds we have knowledge of from ancient Egypt and so, the following article considers some of the birds from ancient Egypt that I find interesting. Selected artwork and hieroglyphic signs will be alluded to, as will mummified remains; modern information, where relevant, will also be included.

The ancient Egyptians were keen observers of the world around them, especially the fauna (and flora) and so they employed all manner of creatures, which they observed in their environment, in their artwork and in their hieroglyphic writing system. Research suggests that more than seventy species of birds can be seen in ancient Egyptian art and, if you consult Alan Gardiner’s Egyptian Grammar sign-list, you will see he includes 63 hieroglyphs which represent whole birds, or parts of them.

Current research suggests there are some 150 species of birds resident and breeding in Egypt and an additional 300 species visit Egypt, during their migration routes. What was the situation in ancient times in Egypt? The wide range of birds in Egyptian art, preserved remains and textual references clearly indicate that the people of Egypt encountered many species of birds and that these birds played an important role in ancient Egyptian society.

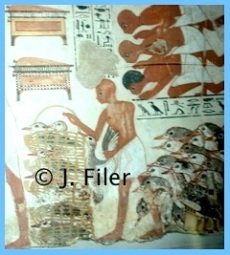

The ancient Egyptians built their homes close to water and in so doing became acquainted with the behaviour of the many birds sharing their environment and, as birds migrated, their seemingly erratic behaviour concerned the Egyptians and it is possible they associated it with chaos, a state of affairs abhorrent to this most ordered of civilisations. Conversely, the many depictions of birds being hunted or captured in containers (see fig. 1) allude to the Egyptian control of their environment and their need for order in their life.

Yet, interestingly, this occupation (bird catching) was derided in the Middle Kingdom Satire of the Trades, as follows:

The bird-catcher, he is very miserable, when he looks at the denizens of the sky. If marsh-fowl pass by in the heavens, then he says: ‘Would that I had a net!’, but god does not let it happen to him…….’

Various sources of evidence show birds in Egyptian religious and social settings: let us now consider a few of these denizens of the sky and marsh-fowl in the ancient Egyptian context.

Raptors: falcons and vultures

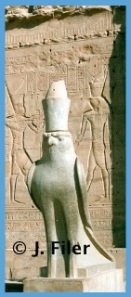

Falcons are probably the most frequently represented bird in ancient Egyptian contexts. Modern tourists arriving in the Temple of Edfu cannot but help notice the magnificent statues of the god Horus, in the form of a falcon, standing proudly in the temple precincts. The statues are about three metres in height and are fashioned in the round. Wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, the example in fig. 2 is formed from grey granite and shows the bird in all his natural glory – ever watchful and alert.

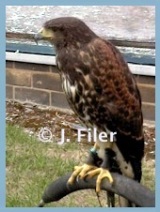

Throughout the development of Egyptian religion, the god Horus has taken on many forms: as Re-Harakte, god of the sun travelling daily across the sky and as Horus the Elder (the Greek Haroeris), the god of light, to name two examples. This latter form of Horus is, perhaps, the one most familiar to those interested in ancient Egyptian religion and myths. Here he is the celestial falcon and a creator god. It is difficult to identify, precisely, which actual falcon represented Horus in Egyptian art; there were several types of falcons in ancient Egypt and, it is possible, that their various features were amalgamated in representations (see fig. 3). Many authorities, however, have postulated that the Peregrine falcon was the most likely species being depicted.

Horus is often seen protecting the living ruler, with his wings spread around the king’s head, offering advice and guidance. Horus represented the ideal young man who supported his parents Osiris and Isis; ever thus, the dutiful son. Egyptian myths tell us Horus went into battle with his uncle Set (who usurped the throne of Osiris) in order to avenge the death of his father, the rightful king of Egypt. During the battle Horus loses an eye, thus the wedjat (or udjat) eye, representing this plucked out orbit, has become the best-known protective amulet. Ancient myths tell us that this amulet was so powerful that, when Horus offered his healed eye to Osiris, his dead father was restored to life. To this day the eye is a powerful protective symbol in Egypt and the Middle East generally and some ancient texts suggest Horus continues this battle throughout eternity in order to protect Egypt from harm.

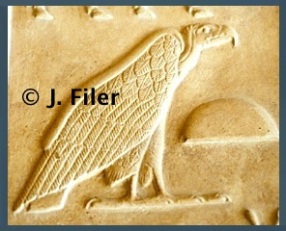

Egypt is home to various species of vulture: the Griffon, the Lappet-faced and the Egyptian, and these are easily identified in Egyptian artistic sources. As with many aspects of Egyptian life there is a dichotomy concerning vultures. On the one hand, the ancient Egyptians linked the birds with terror because they were seen picking at the flesh of dead animals, yet, because the Egyptians observed the excellent motherly instincts of the females, they also associated vultures with maternal care. Indeed, the ancient Egyptian word for mother includes a vulture hieroglyphic sign; a vulture hieroglyphic sign, carved in stone, can be seen in fig. 4.

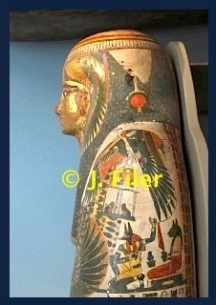

Vultures are particularly associated with two protective goddesses: Nekhbet, who gave protection principally to the king of Egypt and also to his subjects and Nut, the sky goddess. As we can see in fig. 5, a Lappet-faced vulture, here representing the sky goddess Nut, is giving eternal magical protection to the deceased within the coffin by grasping the hieroglyphic sign for ‘infinity’ or ‘forever’; this species of vulture, being extremely powerful, is well-chosen to carry out this important task.

Water birds: ibis and waterfowl

Nowadays, modern travellers will not see the Sacred ibis in Egypt due to the changes in their favoured habitat. They do, however, continue to nest in the Sudan.

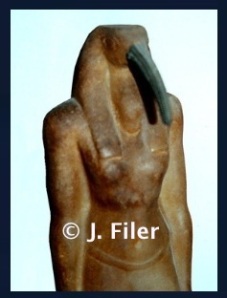

The ibis was associated with Thoth, the god of wisdom, learning and writing (fig. 6); as it was believed that Thoth gave Egyptians the skills to read and write so this species is termed the Sacred ibis because of this link with writing, an art which the Egyptians regarded as absolutely sacred. The other species of ibis known from ancient sources are the Hermit ibis and the Glossy ibis.

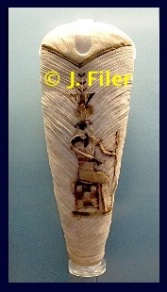

Like the falcons mentioned above, ibis birds were mummified in great numbers. This testifies to their importance in religious beliefs and, indeed, the Greek author Herodotus tells of a royal decree threatening the death penalty for anybody who killed a sacred ibis or a sacred falcon (Herodotus, Book II, 65). The majority of these ibis mummies were linen-wrapped in decorated conical shapes (see fig. 7) and were often inserted into specially prepared pottery jars. To note a case in point: excavations at Tuna al-Gebel (near Ashmunein, the ancient town of Hermopolis, with the well-known temple to Thoth) has revealed the presence of thousands of ibis mummies.

Waterfowl, including wild and domestic species of ducks and geese, were popular items at the table. Evidence suggests that the ancient Egyptians actively bred them to bulk up the numbers of those taken from the wild and this would seem to have been of prime importance to the environment, to go by the numbers recorded as part of temple offerings; Ramesses III, for example, donated over 430,000 individual waterfowl to temples during his thirty-one year reign. Classic authors, such as Diodorus Siculus, writing in the First century AD, describe Egyptian poulterers artificially incubating eggs, in that they

‘raise them by their own hands, by virtue of a skill peculiar to them, in numbers beyond telling…..’ (Diodorus Siculus, Book I, 74)

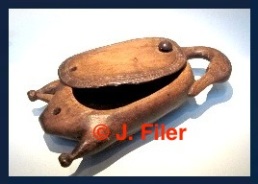

Ducks, as well as being food items, were often incorporated into Egyptian art – on tomb ceilings and as cosmetic unguent holders. The example in fig. 8 is a particularly delightful wooden container in the form of a rather ‘squashed’ looking duck – like the hieroglyphic sign (see Gardiner, Egyptian Grammar, Section G: Birds, sign 54). It has been suggested that images of ducks may also allude to female sexuality and fertility.

Reverence of the goose in Egypt can be attested far back in time – it was believed that the goose (termed ‘the great cackler’) fathered the primordial egg from which the sun was ‘hatched’. Again, the Egyptians were very observant of their environment with regard to the behaviour of geese. The Nile goose is a temperamental creature and often caused damage to growing crops. A scribal writing exercise states that

‘it (the Nile goose) spends the summer ravaging dates, the winter destroying the seed grain ……. one cannot catch it by snaring …… one does not offer it in the temple ……’

On this rather ‘cackling’ note, I shall end these brief notes on Egyptian birds – but it is clear that a lot more can be said about these intriguing members of the natural world.

images: courtesy Joyce M. Filer