by Joyce Filer

(formerly Curator for Human & Animal Remains, Dept. of Ancient Egypt & Sudan, British Museum)

This article serves as a general background to the evidence for famine in various periods of ancient Egyptian history.

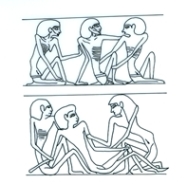

To many people ancient Egypt is not a civilisation linked to food shortages. In antiquity, Egypt was renowned for its agricultural success, so much so that, in later periods, the country was desired by the Romans as a provider of grain. Agricultural productivity was linked to an effective inundation of the River Nile. Every year, the combined forces of the Blue Nile originating in East Africa and the White Nile flowing north from central Africa, flooded the river banks of Egypt depositing rich, black mud on the land; farmers encouraged the further spread of the waters by digging irrigation channels and this practice continues today (fig. 1). Following the lowering of the flood waters, seeds were planted and the ensuing crops eagerly awaited (fig. 2). However, on the occasions when the Nile flooded either too much or inadequately, crop failure would occur and it seems that there were periods of famine.

However, for a culture clearly so keen on recording daily life events, there are relatively few references to famine and starvation in terms of artwork and texts. Interestingly, examinations of ancient Egyptian and Nubian skeletons seems to suggest there could be biological evidence possibly demonstrating famine and starvation. Let us examine the sources.

Artistic and textual evidence for famine

Recording information in ancient Egypt was really a way of expressing an ideal state and perpetuating desired order. By actually recording episodes of starvation and famine, the failure of the authorities to provide food for the people would have been demonstrated, and this surely would have been a foolish political admission by the ruling classes. This may account for why we have relatively few records, artistically and textually, of famine and starvation.

Probably the best known artistic representations of starvation from ancient Egypt are these shown on the causeway leading to the valley temple of King Unas (Wenis). Dating to about 2,500 BC, the scenes show emaciated figures with protruding ribs and pained facial expressions (fig. 3).

It is now thought that these scenes do not depict Egyptians but perhaps people then living on the edges of Egyptian society – that they were Beja people has been suggested. Whatever their identification, it is clear that they are under stress and it is possible they may have come further into Egypt in order to obtain food and thence their suffering was recorded by Egyptian artists.

A text carved on a granite boulder on Sehel Island ( near the first cataract) has been termed The Famine Stele because it includes references to food shortages. The text, purporting to be a decree from the Third Dynasty king Djoser, records the king’s concerns that the Nile’s poor performance for seven years has caused widespread food shortages:

‘I was despondent upon my throne, and those in the palace were in grief. My heart was extremely sad since the Inundation had not come on time for a period of seven years. Grain was scarce, the kernels dried out, everything edible was in short supply.’

Whilst it is possible that the decree is recording actual times of hardship, it is unclear as to when the events actually occurred for examination of the text’s language (grammar, vocabulary) indicates that it was, in fact, composed during the Ptolemaic period but set in the earlier Old Kingdom period.

Information from texts in the tomb of Ankhtifi at Moalla, however, offers information with a more secure date. The First Intermediate Period, at the end of the 3rd millenium BC), in Egypt seems to have been a time of political troubles. The kings of Egypt of the time were based in Herakleopolis but evidence indicates that, due to a rising development whereby local officials became governors, or rulers, of their particular regions, the Herakleopolitan kings held only a loose power over much of the country. We have tomb autobiographies of some of these local governors such as those of Ankhtifi at Moalla and Hetepi at Elkab; that of Ankhtifi is particularly useful in terms of examining evidence for famine.

Ankhtifi was the governor of the nome (or province) of Nekhen which he controlled from his home in the town of Moalla (ancient Hefat). Due to his political abilities he was able to expand his control over two other provinces – Edfu (ancient Khuu) and Elephantine (ancient Ta-Sety) and from this was able to challenge Theban authority over Upper Egypt. Accounts of Ankhtifi’s battles, his confederation of three provinces and the subsequent success of the Theban forces can be read in detail elsewhere, however, what is particularly useful to this discussion is the information Ankhtifi gives us about food deprivation.

A tremendous famine hits the whole region of southern Upper Egypt, affecting Akhtifi’s province and that of other local rulers – as evidenced by the funerary inscriptions of some of these governors. Ankhtifi tells us

‘Upper Egypt was dying of hunger; every man was eating his children’

Ankhtifi’s immediate response is to release food from his stock-piled food supplies, firstly to aid his own area, in which he states ‘nobody died of hunger in this nome’ and then more widely to other parts of Upper Egypt. There can be little doubt that Akhtifi was a saviour to many Egyptians at this time!

Biological evidence for famine

When an individual undergoes periods of stress – perhaps due to famine or febrile illnesses – evidence may be left as markers in the bones. It is suggested that lesions in the eye sockets and on the parietal bones of the skull may be a record of such stress. Some researchers have proposed that these markers are indicators of iron deficiency anaemia, possibly linked to an inadequate diet, however, it should be stated immediately that others do not subscribe to this theory. It is also important to note that it has also been suggested that this expression of ‘anaemia’ may confer cross-immunity to malaria. This is an important issue to consider in areas where malaria is part of daily life.

Traditionally, it is stated that children show more of these ‘anaemic’ lesions than adults and, amongst adults, females show more lesions than males. This has led some researchers to suggest that this pattern reflects food distribution in society – that adults get more (and better) food than children and that males in society receive better food than females (and children); but, can we so easily force this explanation onto ancient Egyptian society? – I am not so sure! There are actually several issues here: who gets the food, how much does he/she receive and, perhaps most importantly, is it the food received nutritious? In theory, you can receive lots of food but if the food does not contain the correct nutrients then you might still display signs of malnutrition. This calls to mind information I was told by a doctor concerning a boy (with parents of quite considerable financial means) who was hospitalised with severe malnutrition and who appeared almost at the point of starvation. It turned out that the boy was seemingly eating large amounts of food but, as it was found out, his parents were often away on business leaving him with a carer and stubbornly (as children often are!) the boy had insisted on choosing his own food – eating only crisps, chips and so on! He became very undernourished and ill but recovered upon receiving a more nutritious diet.

Certainly in keeping with distribution patterns in other ancient cultures, ancient Egypt and Nubia show similar traits in that more children than adults show these ‘anaemic’ lesions and that more females than males exhibit the lesions. Let us now consider these lesions (or markers) and illustrate them with examples from various periods of Egyptian and Nubian history.

The lesions which appear in the upper eye sockets are termed cribra orbitalia (fig. 4).

The example in figure 4 is that of a sub-adult from Gabati (now in modern Sudan). Dating to the post-Meroitic period of Nubian history, the child was only one of many individuals from the site exhibiting such lesions. The markers can be assessed in terms of their severity (mild, severe) and in terms of their different shape formations, as in figures 5 & 6.

Tests undertaken on soft tissue (brain) material have revealed that many groups in ancient Nubia existed on a diet largely of sorghum wheat. Whilst such groups may not have ‘gone hungry’, there are relatively little nutrients in the diet and so these markers may reflect not actual famine but rather inadequate nutrition.

The lesions which appear on the parietal bones of the skull are often termed porotic hyperostosis and, again, are categorised according to their size and shape. Individuals may exhibit lesions in both the eye sockets and the parietal bones or solely in the eye sockets or solely on the skull bones. An 11th dynasty female skull (fig. 7), on display in the British Museum, is thought to be that of a high-ranking Egyptian individual.

Due to her high position in society, we might suppose that she did not want for food yet this woman’s parietal bones show clear evidence of the lesions termed porotic hyperostosis – it may well be that, despite her wealthy position in society, the food she ate was not nutritious enough. Alternatively, it may be an indication that she suffered from bouts of febrile illnesses as a child which then left a record in her skull bones.

Whilst it is interesting to examine individuals from the past it is more useful to examine large groups of skeletons then you can see what biological patterns are emerging to explain ‘behaviours’ in ancient times. From my examinations of many series of Egyptian and Nubian human remains it is quite clear that these two types of lesions can be easily demonstrated – but it is the reason for their occurance which is open to debate. If, as can be demonstrated, many individuals in a cemetery exhibit such markers (either in the orbits, on the parietals or both) then this might suggest some widespread ‘catastrophe’ – such as food shortage over many years, but there may be other reasons of which we are not aware!

To end on a further note of caution – research suggests that these lesions might obliterate during an individual’s lifetime so that some individuals may not show such markers, especially adults who live to a reasonable age. Thus, clearly, the situation of cribra orbitalia and porotic hyperostosis indicating episodes of famine is a complex one demanding further research.

All illustrations courtesy and © of the author.